Puritans were English Protestants who wished to reform and purify the Church of England of what they considered to be unacceptable residues of Roman Catholicism. During the reign of James I, the Presbyterian majority unsuccessfully attempted to impose their ideas on the established English church at the Hampton Court Conference (1604). During the 1620s leaders of the English state and church grew increasingly unsympathetic to Puritan demands. They insisted that the Puritans conform to religious practices that they abhorred, removing their ministers from office and threatening them with "extirpation from the earth" if they did not fall in line. The result was mutual disaffection and a persecution of the Puritans, particularly by Archbishop William Laud, that brought about Puritan migration to Europe and America. Zealous Puritan laymen received savage punishments. For example, in 1630 a man was sentenced to life imprisonment, had his property confiscated, his nose slit, an ear cut off, and his forehead branded "S.S." (sower of sedition).

Those groups that remained in England grew as a political party and rose to their greatest power between 1640 and 1660 as a result of the English civil war; during that period the Independents gained dominance. During the Restoration which followed, the Puritans were oppressed under the Clarendon Code (1661–65), which secured the episcopal character of the Established Church and, in effect, cast the Puritans out of the Church of England.

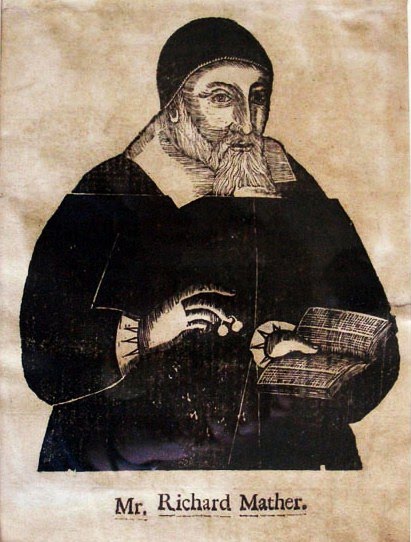

John Foster (1648-1681), Portrait of Richard Mather. Woodcut, first issued ca. 1670. Richard Mather (1596-1669), minister at Dorchester, Massachusetts, 1636-1669, was a principal spokesman for and defender of the Congregational form of church government in New England. In 1648, he drafted the Cambridge Platform, the definitive description of the Congregational system. Mather's son, Increase (1639-1723), and grandson, Cotton (1663-1728), were leaders of New England Congregationalism in their generations.

Beginning in 1630, as many as 20,000 Puritans emigrated to America from England to gain the liberty to worship God as they chose. Most settled in New England, but some went as far as the West Indies. Theologically, the Puritans were "non-separating Congregationalists." Unlike the Pilgrims, who came to Massachusetts in 1620, the Puritans believed that the Church of England was a true church, though in need of major reforms.

Cotton Mather...Mezzotint by Peter Pelham. Boston 1728. Cotton Mather (1663-1728), the best-known New England Puritan divine of his generation, was a controversial figure in his own time and remains so among scholars today. A formidable intellect and a prodigious writer, Mather published some 450 books and pamphlets. He was at the center of all of the major political, theological, and scientific controversies of his era.

Every New England Congregational church was considered an independent entity, beholden to no hierarchy. The membership was composed, at least initially, of men and women who had undergone a conversion experience and could prove it to other members.

Puritan leaders hoped (futilely, as it turned out) that, once their experiment was successful, England would imitate it by instituting a church order modeled after the New England Way.